Juleøl is more than beer. It’s an institution. Here’s the A-Z scoop on Norway’s beloved Christmas ale.

Come December, juleøl (jul meaning Christmas, øl meaning beer) launches a full-scale takeover of Norway’s grocery and liqueur stores. Breweries of all sizes, located all across Norway, produce juleøl for the holiday season.

Norway’s annual ale tradition wasn’t born yesterday; it has quite a history (read: hundreds of years). So, how exactly did this ancient tradition begin?

Before juleøl was juleøl: A short beer history of Scandinavia

Modern-day juleøl is most often a strong, dark ale (though the concept has expanded to a range of beer types).

Winter beer (along with beer in general) has been brewed in Scandinavia since pre-Christian times; only later did it don a Christmas jacket.

So, how did juleøl look before it became juleøl?

Pre-Christian times

Alcohol was always an integral part of pre-Christian Norse culture.

Norse peoples had various fermented beverages, including:

- ale (based on barley)

- mead (based on honey)

- syra (based on milk and considered a lower class drink)

- wine (an imported luxury reserved for the rich)

Ale was likely the most often-consumed alcoholic beverage in ancient Scandinavia.

Scandinavia has brewing traditions thought to date back over a millennium. During the Viking Age and maybe the Iron Age, beer was likely consumed often, as a safer alternative to water in certain regions and while traveling.

At first, making and serving alcohol was solely a woman’s job. In a 13th-century manual on poetry, aspiring poets were advised to refer to women not as women – but as ale crafters.

Drinking had an ingrained cultural value. Alcohol was closely tied to mythology and the gods, who were believed to enjoy it among themselves so much that they decided to gift it to humans, too.

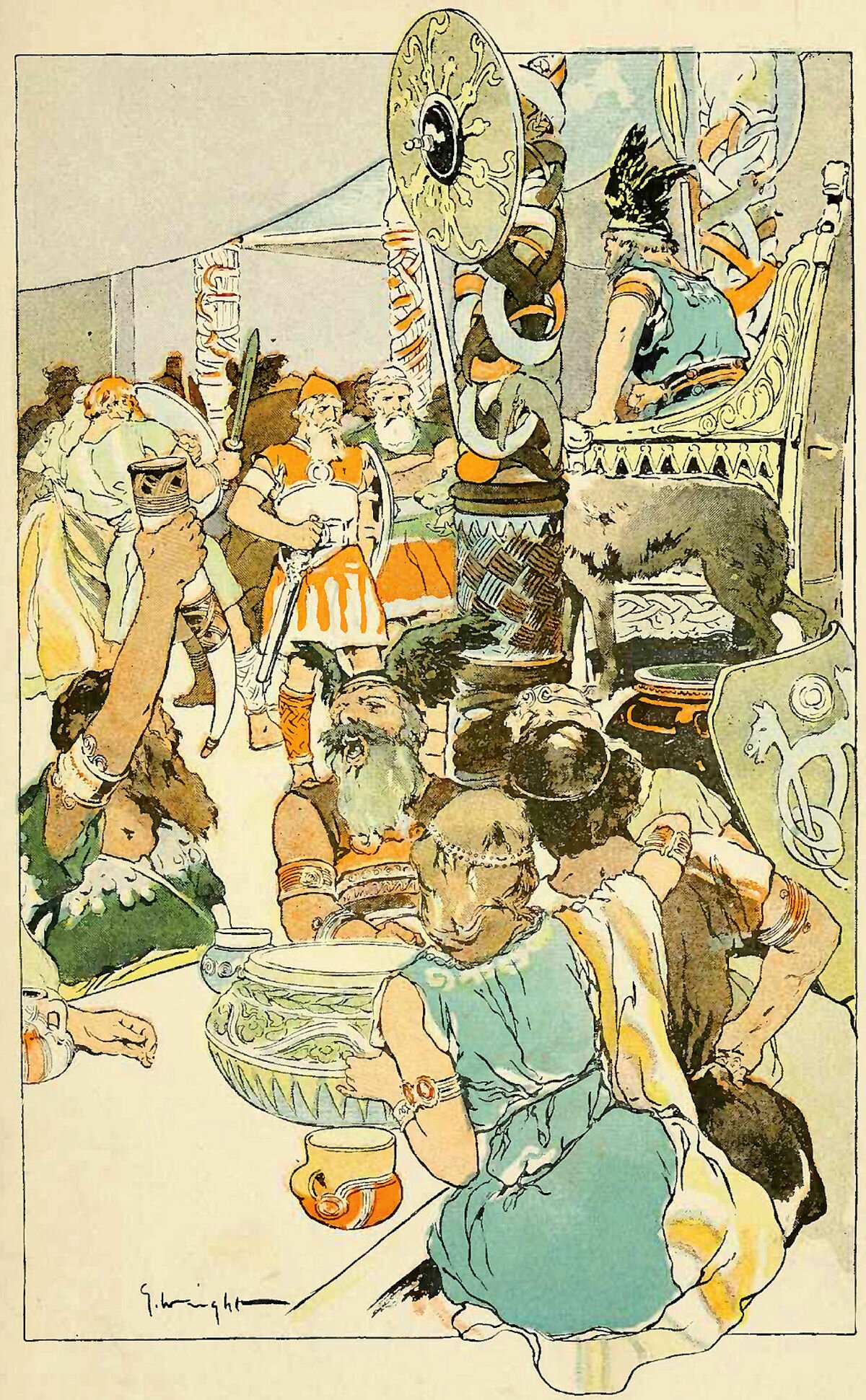

One of the biggest testaments to the importance of alcohol in ancient Norse culture was the concept of Valhalla, the mythical mead hall ruled over by Odin. It was thought that Odin sent his Valkyries (divine warrior maidens) to every battle across the realms. The Valkyries chose the most heroic fallen fighters and brought them to Valhalla for their afterlives.

In Valhalla, the warriors would forever commence in friendly battles with each other and enjoy endless supplies of alcohol.

Where would all this alcohol come from? Infinite streams of mead would pour out from the udder of Heiðrún, a goat in Norse mythology, and into Valhalla.

Beer and mead were consumed by Vikings before they passed on to the afterlife, too – both on regular days, and during events such as marriages and funeral feasts.

Before jul meant Christmas, it denoted a period of celebration observed between November and December. It marked the end of the laborious autumnal harvest. Jul was the time to celebrate and down horn upon horn of juleøl’s pagan predecessor.

Also important mead and ale-focused events were feasts. Chieftains and leaders would hold grand festivities in their mead halls, or hearth rooms – the largest rooms in the Viking longhouse.

One of the most famous examples of a mead hall party can be found in the poem Beowulf (dated to around 700-1000 CE). This alcohol-impelled affair was hosted by King Hrothgar of the Danes.

During both regular meals and feasts, chieftains and leaders symbolically sat in a designated chair at the head of the table. In Norse mythology, the high seat Odin similarly occupied at the head of his heavenly table was called háseti or ondvegi.

The earthly seats of honor were a parallel to Odin’s head seat at the feast table in Valhalla, from which he looked over the warriors celebrating below, as well as the entire world.

Feast guests, along with the rest of the members of the household, sat on the benches (which also doubled as beds during the night) surrounding the hearth room. At hearth room feasts, toasts with beer and mead would have been made to the gods; especially to Odin.

Early Middle Ages

The beginning of the medieval period saw a shift in drinking habits, but alcohol retained its societal importance – even after a few early attempts to squash it.

King Olaf (c. 995 – c. 1030), later Saint Olaf, is often credited with spreading Christianity throughout Norway. He is also thought to be the first who attempted controlling alcohol production and sales. By banning the sale of malt, grains, and corn to the north of Norway, Olaf tried to diminish the power of northern chieftains (and in doing so, increase his own).

One of the chieftains, Asbjorn Siggurdson, had a particularly big problem with that. The story goes, Siggurdson snuck out west to procure the supplies needed to make beer for his father’s funeral feast. He was discovered by Olaf’s steward Sel-Thorir, who confiscated the goods. Later, in 1023, Siggurdson killed Sel-Thorir while Olaf was present (which got Siggurdson the name Selsbane). This event is thought to have influenced Olaf’s loss of power, and, in turn, his death in 1030.

After Olaf, Swedish Prince Eric Magnusson tried to ban alcohol completely, issuing a 1295 charter prohibiting all alcohol production and sales. Norway’s monks found a way around the law, however. The clergy claimed they needed to brew their own beer for religious purposes and for the health of their communities.

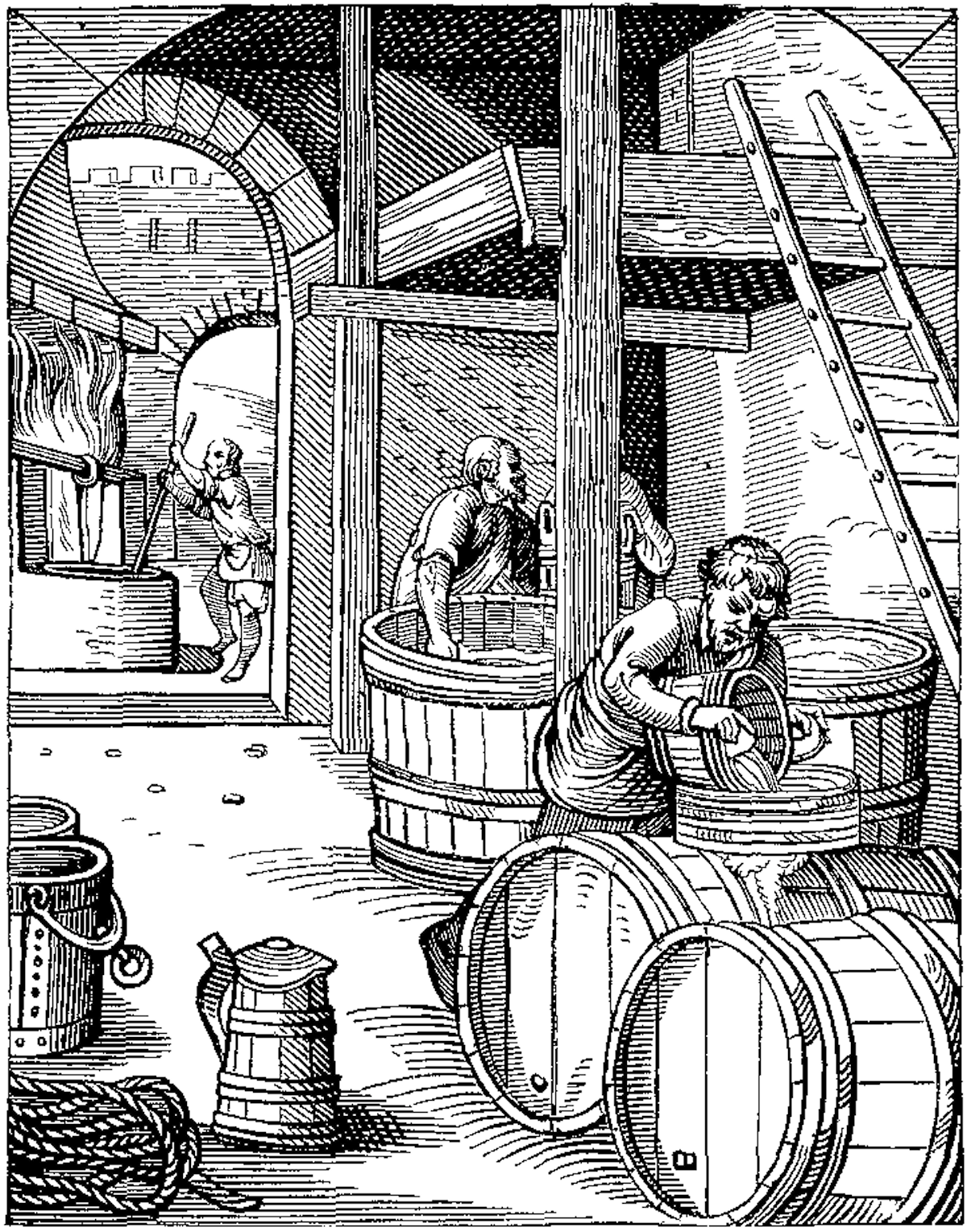

And so, alcohol remained important in Scandinavia even after Christianity triumphed. This time, however, it wasn’t a master brewer making ale out of her own longhouse – it was a Christian monk producing (and consequently blessing) it.

Late Middle Ages

Many Scandinavian farms had their own brewing operation during the late Middle Ages. Such a beer-making site was called bryggehus, meaning brewing house.

Through the 1700s, all types of brewing in Scandinavia, from that done by farmers to the clergy, were producing fairly similar types of beer.

1800s

Beer in Norway underwent a big transformation in the 1800s, when large-scale commercial brewing came into play.

Norway saw its first official brewery open around 1800 in Oslo (then Christiania). By 1857, Norway had over 340 breweries. Around this time, the Norwegian government also began to regulate beer-making.

This is when Christmas beer, as a standalone product, started to crystallize. Though advertising of beer and other products was already underway, the first commercial advertisements for juleøl – as such – are thought to have appeared in the 1860s and 70s.

At the end of the 1800s, what we know today as Christmas beer had emerged as a clear concept.

From the beginning, juleøl wasn’t any specific kind of beer; rather, it was a concept. Juleøl generally referred to any beer that was sweeter and stronger than everyday ale, and that was considered a good pairing for Christmas foods.

1900s

During the interwar period of 1918-1939, Christmas beers skyrocketed in popularity. Why?

Norway’s Brewery Association divided the country up into beer monopolies by region. While beers were largely standardized during this time, creativity in ale advertising soared.

During WWII, juleøl production ceased because brewers’ resources were depleted. Beers that were produced during this time were largely weak and bland – much unlike Christmas beer as we now know it.

The resource-hungry juleøl (this is no basic beer; it takes time and supplies to make) didn’t enter mass production again until the 1950s.

The mid-1970s saw the Norwegian government ban all advertising of alcohol. So, any vintage juleøl ads you come across are truly remnants of times bygone.

During the 1980s, the brewery monopoly system collapsed and competition again stirred among beer producers across the country. In 1987, Norway had 15 breweries – but this number would soon catapult.

2000s

In 2003, Norway’s law regulating alcohol production was amended to include microbreweries. Today, around 100 microbreweries operate all across the country.

The world’s northernmost microbrewery sits on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, which is situated halfway between the mainland and the North Pole.

Of about a dozen corporate breweries, two large- and three medium-sized companies are most well-known today:

- Ringnes, Norways largest brewery, is owned by Carlsberg of Denmark.

- Hansa-Borg, based in bergen, is Norwegian owned.

- The medium-sized players are Aass of Drammen, Grans of Sandefjord, and Mack of Tromsø.

Buying juleøl in Norway

Alcohol regulations in Norway

You have to be 18 to buy wine or beer in Norway. To purchase hard liquor, you must be 20.

Licensed restaurants, bars, and clubs sell alcohol.

For home purchase, some shops also sell beer and cider, but only if it’s up to 4.7% ABV. For any beer over that percentage, for wine, and for spirits (which Norway regulates as anything over 22 ABV) – you’ve got to head to Vinmonopolet (literally meaning, “The Wine Monopoly”), a state-run alcohol store.

Vinmonopolet working hours can vary from store to store, but none are open on Sundays, and they usually close before the evening on Saturdays. These shops are usually found in larger cities, so those from rural areas might have to travel quite a bit before being able to enjoy a bottle of juleøl back at home.

It’s hard to rank which Christmas beer is best – that depends on everything from taste and mood to region.

Either way, you have countless large-scale producers and microbreweries to choose from. You’d be hard-pressed to find a Norwegian brewery (no matter its size) that doesn’t create its own juleøl.

The Christmas beer is so popular in Norway that failing to produce it would be not only a marketing miss – but also a disappointment to the shoppers that eagerly choose from a wide selection of this awesome ale each year.

Other holiday drinks in Norway

Not a fan of beer, or seeking to switch it up a bit? Here are a few other drinks that’ll also have you feeling festive (some more than others maybe) during the holiday season.

Juleaquavit: Christmas aquavit is a festive take on aquavit, a distilled, herb-flavored spirit popular in Scandinavia. Aquavit’s holiday edition is usually spiced up with Christmas flavors like vanilla.

Julebrus: Christmas soda is a twist on juleøl for minors and non-alcohol drinkers. The tasty soft drink usually comes in red, or in brown, beer-like colors. Many breweries in Norway will offer julebrus alongside their juleøl.

Gløgg: This is the Scandinavian answer to mulled wine. Think warm wine, aromatic spices, and, if you’re sipping in Norway – sliced almonds and raisins served right in the glass.

To conclude…

Now that you know all about juleøl – be sure to have yourself a merry little Christmas (beer).

Source: Norway Today

Leave a comment